Unit Stills Photographers

Cecil B. DeMille saw that movie-fan magazines were proliferating after World War I. He realized he could better sell his films if he supplied high-quality photographs to these publications, and he began to hire fine-art photographers. When the “unit stills man” said “Hold for stills,” the average director, impatient to create the next setup, told him to hurry. DeMille allowed the photographer both time and artistic license, and would occasionally step in and direct the photo himself.

One of the first camera artists hired by DeMille was New York-born Karl Struss, a Columbia University graduate and a distinguished member of Alfred Stieglitz’s Photo Secessionists who had recently co-founded the Pictorial Photographers of America. When Struss arrived in Hollywood, he worked as both a unit stills photographer and second cameraman, but soon found himself in demand as a “first cameraman,” a cinematographer.

When DeMille hired Kales to make portraits rather than scene stills, the University of California-Berkeley graduate was known as an advertising agent, songwriter, and playwright. He was also a member of the Camera Pictorialists of Los Angeles, using a soft-focus lens to create highly diffused photographs.

Edward Curtis maintained a portrait studio in his apartment on Rampart Boulevard in the artsy Westlake District of Los Angeles, but he was best known for his monumental research and volumes of photographic documentation of Native Americans. This led DeMille to use him on Adam’s Rib (1923). DeMille’s next film, The Ten Commandments (1923), was a mammoth production, so Curtis joined several fine-art photographers to create publicity art.

By 1922 the Hollywood film industry had a few veteran publicists and photographers, one of whom was Donald Biddle Keyes. His imaginative work on the DeMille films at Famous Players-Lasky led to the opening of a portrait studio at the newly formed Paramount Pictures.

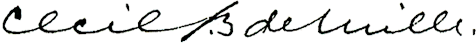

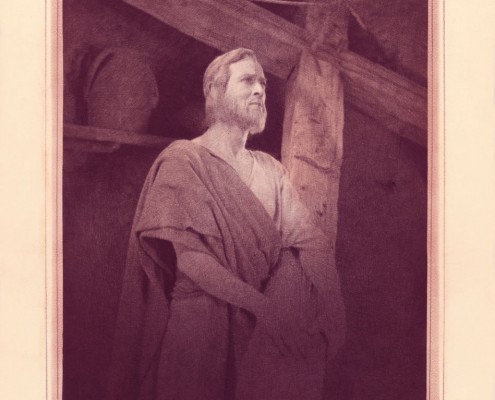

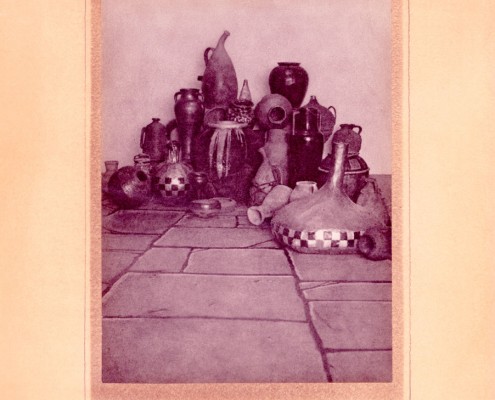

The Utah-born artist was introduced to DeMille by the painter-photographer-director Ferdinand Pinney Earle, who had worked on M-G-M’s Ben-Hur. DeMille hired Mortensen to shoot both scene stills and special art for The King of Kings (1927). It was a fortuitous connection. Few American photographers could have distilled the reality created on the set by Mitch Leisen and Pev Marley as Mortensen did. To lend a painterly quality to his images, he placed hand-etched filters over the photographic paper as he printed each negative in his Hollywood Boulevard studio. The result was a reverent, masterly portfolio, unique even for the period. Mortensen opened a photography studio and school in Laguna Beach in the 1930s, co-authored numerous books, and in 1949 was awarded the prestigious Harold Hood Medal by the Royal Photographic Society.

William Thomas worked at various studios from the 1920s through the 1950s, but his work on two DeMille epics is exceptional. He imbued scene stills with the depth of portraits, and he gave production stills painterly compositions.

Although Ray Jones was working as a unit stills photographer on Cleopatra, he found opportunities to make portraits of the principals. In 1936 he became head portrait photographer at Universal Pictures, a position he held for thirty years.

DeMille hired Richardson from the ranks of the Paramount still photographers in 1938 for The Buccaneer, and Richardson worked with DeMille through his last projects.

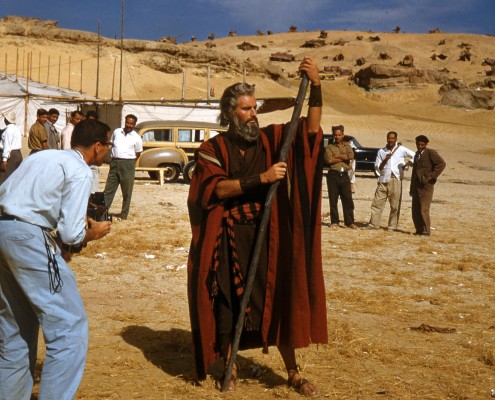

Art student and Korean War vet Ken Whitmore was discovered by actress Joan Woodbury at the Kaminski Creative Photo School in Brentwood. Woodbury got Whitmore an interview through her husband, Henry Wilcoxon, who was DeMille’s associate producer. DeMille liked Whitmore’s work, so he went to Egypt with the Ten Commandments company, shooting angles and scenes that were not covered by G.E. Richardson, the union stills photographer assigned to the film.