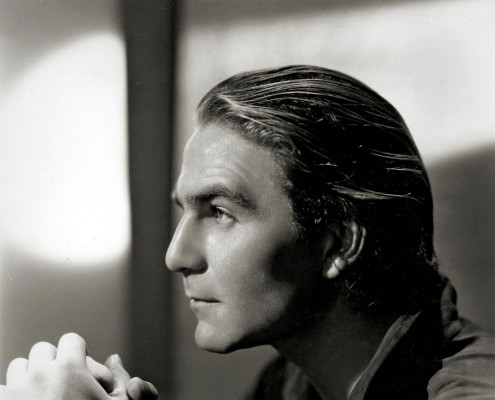

Portrait Photographers

Just as the unit stills photographer became crucial to the marketing of a film, so did the studio portrait photographer become a vital element of the selling of a star. Thus the portrait artists at each studio shot glamour portraits not only of DeMille’s newest star but also of DeMille.

Paramount was still known as Famous Players-Lasky in 1921, when Eugene Richee joined it to assist Don Keyes in the newly formed portrait department. Richee became head portrait photographer a few years later, and in the 1930s made portraits to publicize many of DeMille’s epics. In 1941 a studio shakeup replaced the entire staff of the Paramount publicity department. Richee found work at Warner Bros. and M-G-M, shooting both portraits and production stills.

When Cecil B. DeMille began his term at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in September 1928, the publicity department had him visit Ruth Harriet Louise’s portrait gallery.

A year after DeMille’s arrival at M-G-M, Ruth Harriet Louise retired. Her replacement as head of the portrait department was a twenty-six-year-old photographer who had been recruited from an atelier in the Westlake District after making spectacular portraits of Norma Shearer. Hurrell was not impressed by stars, but he made many engaging poses of DeMille in May 1930.

Another employee of the early portrait studio at Famous Players-Lasky was Otto Dyar, whose portraits are recognizable because he preferred to use of arc lights rather than incandescent lights to illuminate his portraits.

DeMille invited the celebrated fashion photographer George Hoyningen-Huene to the set of Cleopatra. The British photographer was in Hollywood for Vanity Fair and Vogue.

DeMille also invited the commercial color photographer Paul Hesse to the set of Cleopatra so that an image of Claudette Colbert could be captured in the new carbro color process.

When John Engstead, who was head of the Paramount publicity department, hired William Walling in 1933, the young man had been both an actor and photographer. Walling worked well with new Paramount players such as Henry Wilcoxon and became as skilled as Richee in the use of subtly shaded portrait lighting.

In the 1940s the Paramount Pictures portrait gallery was headed by Whitey Schafer, who continued the soft-focus glow popularized by Josef von Sternberg in the 1930s. This was the Paramount look through Schafer’s death in 1951.

Second-in-command Bud Fraker took over for Whitey Schafer in 1951, continuing the diffused look of Paramount portraits, except when shooting color for magazines.