Biography

Overview

Cecil Blount DeMille was a founder of the Hollywood motion-picture industry, one of the most commercially successful producer-directors of his time, and one of the most influential filmmakers in history. Between 1914 and 1956, he made seventy feature films; all but seven were profitable. Cecil B. DeMille is synonymous with religious epics: The King of Kings, Samson and Delilah, and The Ten Commandments (1956). He blended spectacle, sex, and spellbinding narrative to convey a message of faith.

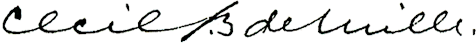

It was DeMille who created the image of the omnipotent director, megaphone in hand, wearing boots and a visored cap. DeMille gave Hollywood numerous stars: Wallace Reid, Gloria Swanson, William (“Hopalong Cassidy”) Boyd, Claudette Colbert, Robert Preston, Jean Arthur, and Charlton Heston.

DeMille created the posts of studio story editor, art director, and concept artist. He was one of the first to use theatrical lighting on a movie set. In the late 1920s, when Hollywood converted to sound films, DeMille defied the sound experts, liberating the camera from a confining booth, and implementing the microphone boom.

DeMille’s authority extended beyond the confines of his studio. He was a power in aviation, banking, politics, and real estate. In the 1930s, his fame as a filmmaker was surpassed by his fame as a radio star.

He was a founder of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, an institution from which he eventually won two awards. In 1953 his film The Greatest Show on Earth won the Award for Best Picture of 1952; and he was presented with the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award.

DeMille’s influence on world culture is incalculable, but there are estimates and milestones. His biography of Jesus Christ, The King of Kings, was a silent film, but because of a unique distribution arrangement, it was eventually seen by 800 million viewers. Samson and Delilah (1949) and The Ten Commandments (1956) are still listed with the top ten all-time box-office champions. They continue to generate revenue and provoke thought.

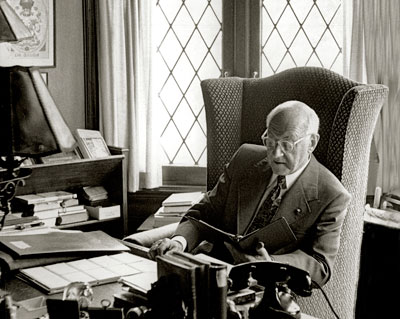

Cecil B. DeMille directing The Ten Commandments in Egypt, November 1954. Portrait by G.E. Richardson

Cecil B. DeMille, the image of the Hollywood director. Portrait by Witzel

Birth and Lineage

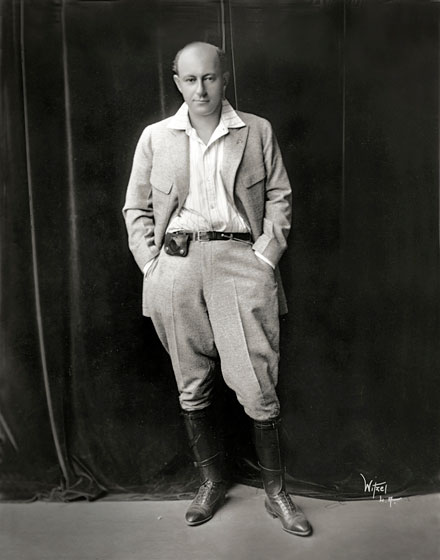

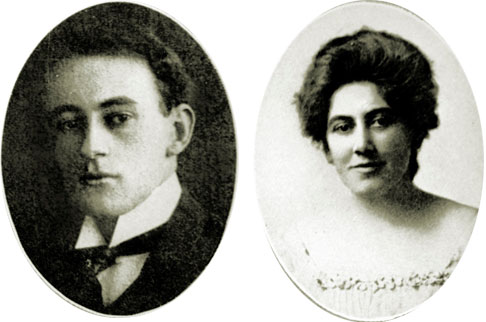

Cecil B. DeMille was born on August 12, 1881, in Ashfield, Massachusetts. His father, Henry de Mille, was born in Washington, North Carolina, of Dutch and English ancestry. Henry was an Episcopal lay minister and a successful playwright.

DeMille’s mother was born Beatrice Samuels to German-Jewish parents in London but was raised in New York. Before her marriage to Henry de Mille, she converted to the Protestant Episcopal faith. Beatrice was an educator and later became the second female play broker in America.

Cecil had an older brother William (born 1878), and a sister Agnes (1891-1895).

Henry & Beatrice de Mille

The DeMille Name and its Variants

Cecil used the spelling DeMille in his professional life, and de Mille in private life. The family name de Mille was used by his daughter Cecilia, and given to his adopted children, John, Katherine, and Richard. It was also used by Cecil’s brother William, and by William’s daughters Margaret and Agnes. It is used by his granddaughter Cecilia de Mille Presley.

Early Years

DeMille’s childhood was memorable for sojourns in a rented house at Echo Lake, New Jersey. It was here that he learned to love nature, through the flora and fauna of the lake. He was introduced to the dramatic arts as he watched his father write plays with the acclaimed David Belasco. Henry often asked Cecil and William for their opinions of the latest draft.

In the evenings Henry read to his children, first from the Bible and then from either a literary classic or a history book. Cecil learned the connection between preaching and the theater. In 1892 the close-knit de Mille family moved to a newly built house in Pompton Lakes, New Jersey.

In 1893 tragedy struck when Henry de Mille fell ill with typhoid fever and died. Two years later the infant Agnes died of spinal meningitis. Beatrice de Mille converted the Pompton Lakes home to a school for girls. She sent William to Columbia University and Cecil to the Pennsylvania Military College. Cecil then studied acting at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, where Henry had taught. Cecil graduated in 1900.

Cecil de Mille as a child

Stage

DeMille made his Broadway acting debut on February 21, 1900, in the Cecil Raleigh comedy Hearts Are Trumps. He appeared in about ten plays, and then grew interested in writing and directing. By this time his brother William de Mille had become a successful playwright and Cecil worked on plays with him.

Marriage and Family

While on tour with Hearts Are Trumps in Washington, D.C., DeMille met an actress named Constance Adams. They were married on August 16, 1902. Their daughter Cecilia was born on October 5, 1908.

Cecil and Constance

Playwriting

The Genius, DeMille’s first play, was produced in 1906. Because he was working in the out-of-style idiom of melodrama, he was unable to score a hit. His did have success in 1907 with his brother and The Warrens of Virginia. In 1911 DeMille wrote a play for his father’s friend, David Belasco, who was by then a power on Broadway. The Return of Peter Grimm was a success but Belasco reneged on credit. DeMille returned to work with his mother Beatrice at her agency, the De Mille Play Company.

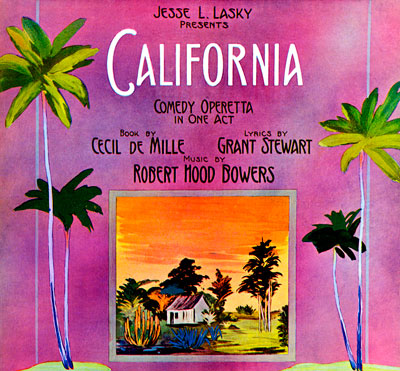

Collaboration with Jesse Lasky

In October 1911 Beatrice de Mille introduced Cecil to Jesse L. Lasky, a San Francisco native who had worked his way up from a vaudeville cornettist to producing shows. Lasky was hoping to engage William de Mille to co-write miniature musical comedies. Beatrice pushed Lasky in Cecil’s direction.

Lasky and DeMille hit it off, since they both had great enthusiasm for playwriting and for the theatre. Their first project, an operetta called California, was a hit, yet thirty-year-old DeMille wanted success on his own. Between 1911 and 1913, he had several flops. By mid-1913, he was considering a career as a war correspondent in Mexico.

DeMille’s first collaboration with Jesse L. Lasky was a stage musical.

The Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company

Jesse Lasky’s sister Blanche had retired from vaudeville to marry Samuel Goldfish, a prosperous glove salesman. (He later changed his name to Samuel Goldwyn). Lasky and Goldwyn proposed that DeMille forget about plays and try moving pictures. DeMille was at first skeptical of this crude form of entertainment, but he saw the potential for both art and profit. In July 1913 he joined Lasky, Goldwyn, and an attorney named Arthur Friend to form the Jesse L Lasky Feature Play Company.

The First Feature Film Made in Hollywood

In the fall of 1913 DeMille suffered two more theatrical disappointments. At his usual lunch in the Claridge Grill, he reported his progress to his best friends—Jesse Lasky, Sam Goldwyn, and Arthur Friend. On November 23, 1913, Lasky proposed that their company make a film version of The Squaw Man, a long-running stage hit.

Goldwyn sent DeMille to the Edison Studio in the Bronx to see how “flickers” were made. He came away confident that he could direct better than the filmmakers he observed. On December 12, DeMille set out for California with stage star Dustin Farnum, a crew, and a co-director, Oscar Apfel. Legend has it that DeMille wanted to shoot his Western in Arizona but was prevented from doing so by a range war, snow, or rain. In fact, there was no impediment in Flagstaff but the scenery. DeMille thought it colorless and boring, so he re-boarded the train for Los Angeles.

When DeMille arrived at the Alexandria Hotel in downtown Los Angeles, an actor friend from his touring days recommended a rental studio in a rural suburb called Hollywood. The studio turned out to be a barn, but it had a laboratory and offices, so DeMille asked Lasky and Goldwyn for a go-ahead.

On December 29, 1913, DeMille and Apfel began filming The Squaw Man. The first feature film shot in Hollywood was completed on January 20, 1914. DeMille edited the film in time for a February 17 preview at the Longacre Theatre in New York. There was, however, a problem with incorrectly perforated film stock. In spite of everything, the Squaw Man achieved success beyond anyone’s expectations.

DeMille made The Squaw Man, Hollywood’s first feature film, in a barn at the corner of Vine Street and Selma Avenue.

The cast of The Squaw Man (1914).

Early Films

DeMille used revenue from The Squaw Man to accelerate production, and he made thirty films between 1914 and 1917. During this period, he and his artists created the lexicon of filmmaking.

The Crucial Merger

On June 28, 1916, the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company joined (1) the Hobart Bosworth Company and (2) Adolph Zukor’s Famous Players Films Company to sign with (3) the Paramount Pictures Corporation, a producing-and-distributing combine run by W.W. Hodkinson.

Adolph Zukor saw the future of the motion-picture industry in terms of a vertically integrated monopoly: a company must control production, distribution, and exhibition. Zukor began consolidating power to himself, ousting both Hodkinson and Samuel Goldwyn, a founding member of the Lasky-DeMille company.

The Famous Players-Lasky partners: Jesse L. Lasky, Adolph Zukor, Samuel Goldwyn, and Cecil B. DeMille.

DeMille’s First Epics

The Paramount merger enabled DeMille to make films on an epic scale, but Joan the Woman (1916) cost so much that it could not make a profit. DeMille rebounded with social dramas and marital comedies that were so profitable that he could add an epic approach to the formula. Male and Female (1919) featured a spectacular shipwreck and a flashback to ancient times. It became the first million-dollar-grossing Hollywood film.

At this time DeMille began hiring fine-art photographers such as Karl Struss to work as unit stills photographers on his films. He allowed them more time and latitude than was customary, seeing that these sensual images lured patrons to his films.

A Karl Struss scene still of Gloria Swanson in Male and Female (1919)

Business

In May 1919 DeMille started Mercury Aviation, the first commercial airline in California. He was also president of the Bank of Italy, Culver City branch (later the Bank of America).

The Roaring Twenties

By 1921, DeMille was the most successful producer-director in America. He had surpassed the legendary D. W. Griffith by tackling the issues of the decade: Prohibition, materialism, women’s rights, sexuality, and divorce. When scandals rocked Paramount, DeMille answered critics with a mammoth morality tale, The Ten Commandments. It brought DeMille more power—and more resentment. He had completed his forty-seventh film when, on January 9, 1925, Adolph Zukor pushed him out of the company he had co-founded.

On March 2, 1925, DeMille opened a studio in Culver City, making his own films and producing those of other directors, a business model that lasted only three years. This period was notable for The King of Kings, a majestic and reverent depiction of the life of Christ that reached an audience of unprecedented size.

On August 2, 1928, DeMille signed a three-picture deal with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, just as talking pictures were taking over Hollywood. DeMille refused to obey the dictates of sound engineers and voice coaches, maintaining that movies should move. His first “talkie” was Dynamite (1929). Its use of moving camera and sound effects made it a hit. The Sound Revolution was followed by the Great Depression. DeMille’s next films failed and he left M-G-M, traveling to the Soviet Union and Europe to study new cinematic techniques.

A scene from The Ten Commandments (1923)

DeMille poses on the set of Dynamite (1929) with the newly blimped sound camera and the silent-film camera he used on The Squaw Man.

Hollywood in the Thirties

In 1932, braving industry hostility, DeMille returned to Paramount and made a remarkable comeback. The Sign of the Cross (1932) was a new type of epic, conveying the best elements of his earlier hits with the aesthetics of sound film.

DeMille continued in this vein, creating an epic hit with Cleopatra (1934). Then he switched gears, focusing on Americana with The Plainsman (1936) and Union Pacific, which was second only to Gone With the Wind in 1939 grosses.

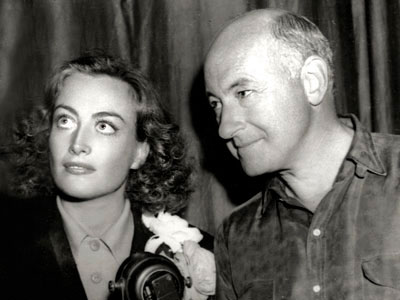

On June 1, 1936, DeMille directed and hosted the first Hollywood broadcast of Lux Radio Theatre, one of the top five programs on the air.

A scene from The Sign of the Cross (1932)

A scene from The Plainsman (1936)

Joan Crawford was a guest star on DeMille’s Lux Radio Theatre in 1936.

Box-Office King in the Forties

DeMille had an unbroken string of American history hits in the 1940s, all in the newly perfected Technicolor process. He ended the decade with a Biblical blockbuster, Samson and Delilah (1949). The DeMille formula of sex and religion brought grosses of $11 million ($108 million in 2016 dollars). Samson and Delilah was the third-highest-grossing film to that date.

A scene from Samson and Delilah (1949)

Legend Triumphant in the Fifties

When DeMille turned seventy in 1951, he was producing and directing his most physically demanding film yet, a semi-documentary circus film called The Greatest Show on Earth. Its $12-million box office was matched by the honor of the Academy Award® for Best Picture of 1952, and DeMille was honored with the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award.

After these back-to-back achievements, DeMille inexplicably met opposition when he proposed an epic on the life of Moses. His one-time nemesis Adolph Zukor helped him win approval, though, and DeMille went to Egypt to film the story at Luxor and on the slopes of Mount Sinai.

On November 7, 1954, while directing 8,000 extras in the desert at Beni Suef, DeMille suffered a severe heart attack. He was seriously ill but, fearing a publicity nightmare, he never missed a day on the set. He recuperated briefly in Los Angeles before shooting studio interiors.

The Ten Commandments premiered at New York’s Criterion Theatre on November 8, 1956, shattering box-office records and gaining a unique cultural significance. With this film, DeMille achieved a lifelong goal. He used entertainment to send a message of faith to a worldwide audience. The Ten Commandments is number seven on the list of all-time worldwide adjusted gross, having earned $2.09 billion.

The grand total of Cecil B. DeMille’s box-office grosses, when adjusted for inflation, comes to $30 billion.

Cecil B. DeMille directs Charlton Heston as Moses in The Ten Commandments (1956)

Last Days

Although The Ten Commandments was his last film, DeMille continued developing scripts through 1958, including a space exploration epic and a biography of Lord Robert Baden-Powell, the founder of the Boy Scouts.

On January 21, 1959, aged seventy-seven, Cecil B. DeMille succumbed to heart failure.

He was survived by his wife Constance; by his daughter Cecilia de Mille Harper; by his adopted children, John, Katherine, and Richard; and by his grandchildren Peter Calvin, Cecilia de Mille, and Joseph Harper. Mr. DeMille was interred in Hollywood Memorial Cemetery.