The Legacy of Cecil B. DeMille

The Director as Superstar

Cecil B. DeMille used his own celebrity to create the prototype of the superstar director. The actor he was in his youth never left him, and he played to the crowds on his sets as he had once played to Broadway audiences. Surrounded by a potentate’s entourage, he garnered publicity by dressing in puttees and open-throat shirts, exhibiting a flair that became the popular image of the movie director. He narrated his films, appeared in their trailers, and portrayed himself in other directors’ films, most notably Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950).

DeMille achieved a unique celebrity as director and host of Lux Radio Theatre, presenting radio adaptations of popular films from 1936 to 1945. On peak Monday nights, as many as 40 million people tuned in. Converted to current television numbers, this represents a bigger percentage than the Superbowl.

In 1950 Picturegoer Magazine called DeMille “the best known movie-maker of them all.” Accounts of what he said and did while shooting his films became part of Hollywood folklore. While many tales were apocryphal (“Ready when you are, C.B.”), DeMille’s lordly comportment was the bedrock of his contribution to cinema history.

An uncredited portrait of DeMille made in 1933

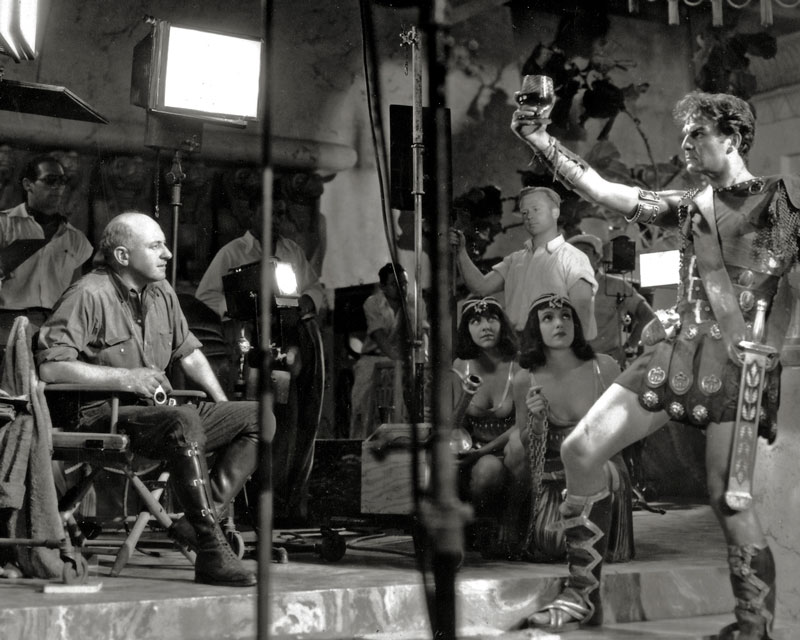

DeMille showing a player how to be a star in Cleopatra (1934)

A Founder of Hollywood

The Squaw Man (1914) was more than DeMille’s debut film or the first feature-length film made in Hollywood—and much more than a critical and financial success. As Joel W. Finler wrote in The Movie Directors’ Story, it “accelerated the trend toward establishing California as the new home of movie-making.”

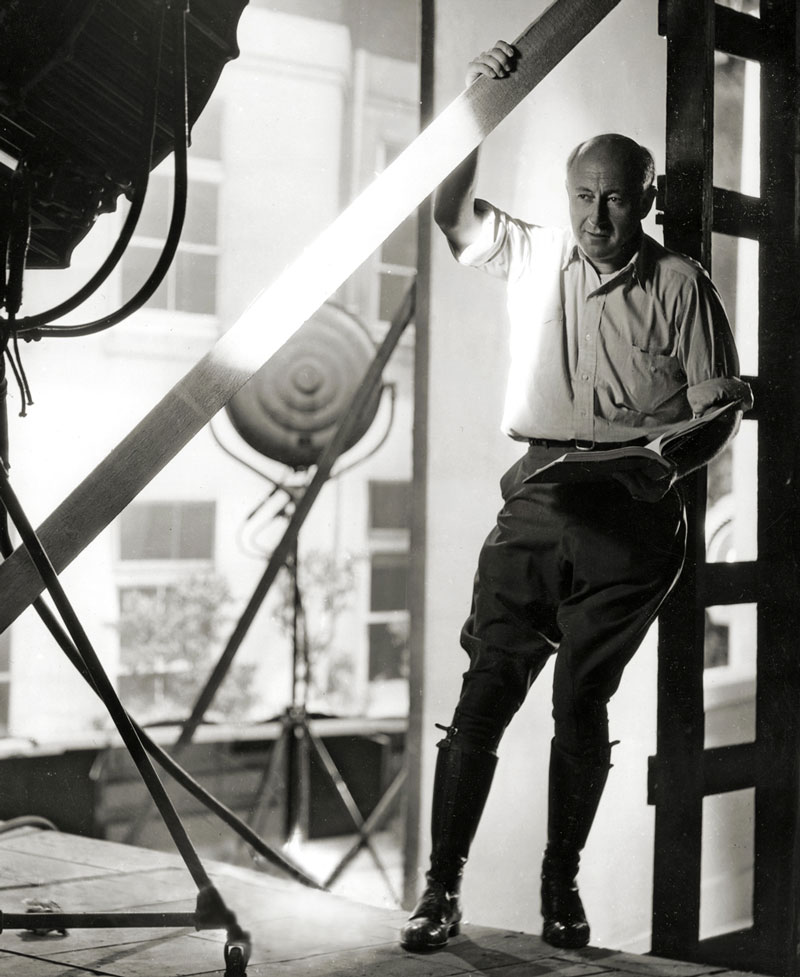

DeMille (in circle) with co-director Oscar Apfel and Dustin Farnum (above) on the set of The Squaw Man (1914)

Photographic Innovator

In The Film Daily’s biographical sketches of directors (July 1, 1928), DeMille was already being credited with “the first developments in lighting and photography.” While shooting The Warrens of Virginia (1915), DeMille had experimented with lighting instruments borrowed from a Los Angeles opera house. When business partner Sam Goldwyn saw a scene in which only half an actor’s face was illuminated, he feared the exhibitors would pay only half the price for the picture. DeMille remonstrated that it was Rembrandt lighting. “Sam’s reply was jubilant with relief,” recalled DeMille. “For Rembrandt lighting the exhibitors would pay double!”

DeMille used an elevator to achieve a crane-like shot in The Godless Girl (1928)

Creator of the Post of Art Director

In Kenneth MacGowan’s Behind the Screen: The History and Techniques of the Motion Picture, Carmen (1915) and The Cheat (1915) are cited as “two of the best examples of DeMille’s reforms in settings and lighting,” incorporating dynamic composition, avant-garde décor, and color tinting. By hiring Wilfred Buckland, DeMille gave Hollywood its first art director.

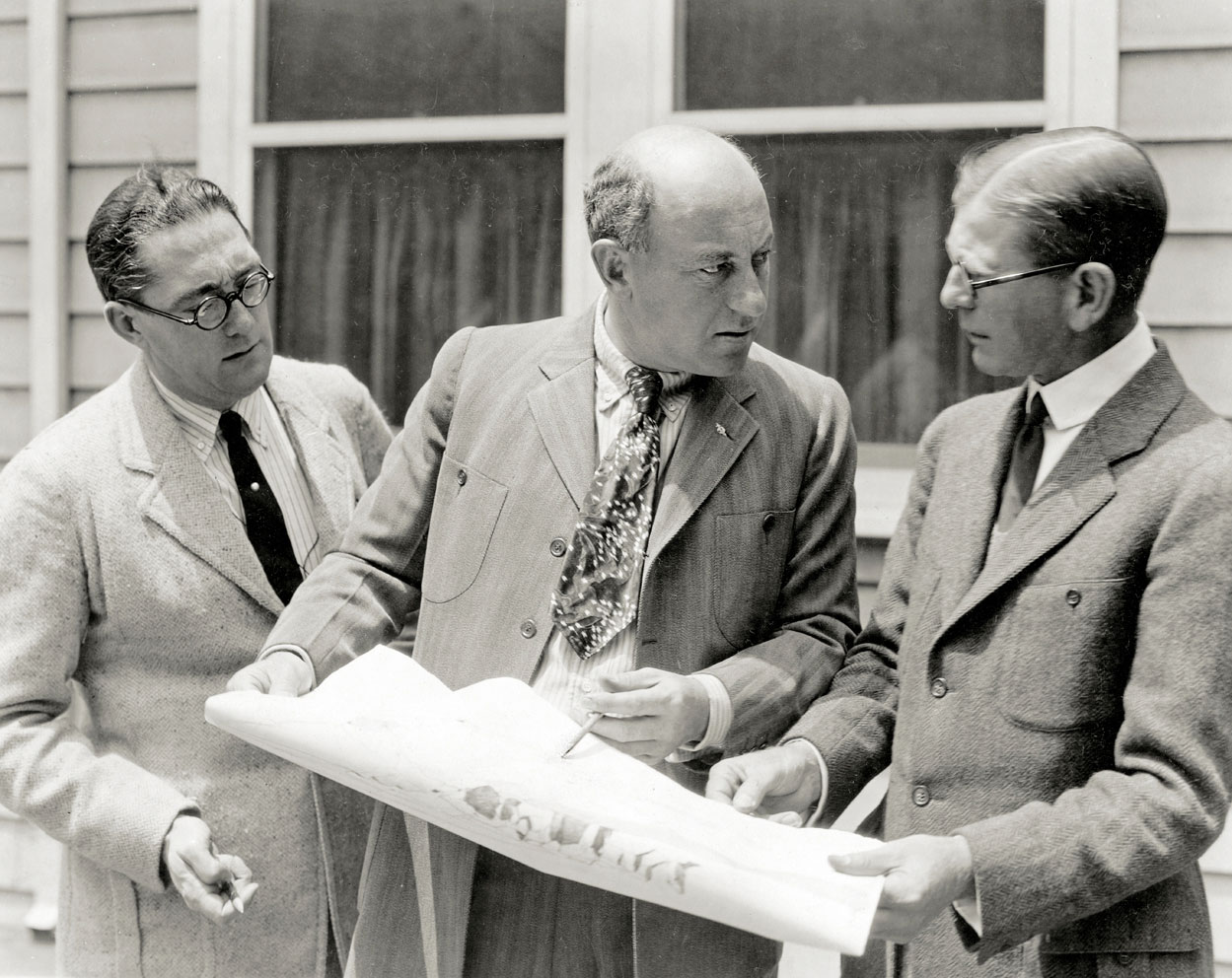

DeMille with art directors Paul Iribe and Francis McComas, 1923

Patron of Artists

DeMille’s childhood exposure to art led him to espouse talents such as Mitchell Leisen, Walt Disney, Edith Head, Gilbert Adrian, Dan Sayre Groesbeck, John Jensen, and Arnold Friberg. DeMille’s emphasis on fashion and design influenced the industry and affected consumerism. Film historian John Kobal called DeMille “a modern Medici.” He recruited artists but gave them the freedom to create.

DeMille reviews concept paintings by John Jensen, 1948

Starmaker

DeMille was a proponent of studio stock companies, using both stars and character actors repeatedly. He was best known for casting untried talent and the cultivating them into stardom. DeMille discovered or developed Elliott Dexter, Theodore Roberts, Sessue Hayakawa, Geraldine Farrar, Gloria Swanson, Wallace Reid, Richard Dix, Thomas Meighan, Bebe Daniels, William (“Hopalong Cassidy”) Boyd, Charles Bickford, Henry Wilcoxon, Robert Preston, and Evelyn Keyes. DeMille gave Charlton Heston his breakthrough role as the circus manager in The Greatest Show on Earth (1952).

In addition, DeMille helped start the careers of directors Mervyn Le Roy, Henry Hathaway, Howard Hawks, Sam Wood, John Farrow, and William K. Howard; and he guided others, such as George Sidney. DeMille introduced choreographers Theodore Kosloff and LeRoy Prinz to films.

DeMille also helped blacklisted artists return to work. These included Miriam Deering and Edward G. Robinson, who wrote: “Cecil B. DeMille returned me to films. Cecil B. DeMille restored my self-respect.” Academy Award winning composer Elmer Bernstein, to whom DeMille entrusted the score of The Ten Commandments (1956), said in numerous interviews that he owed DeMille “everything.”

DeMille on the set of The Affairs of Anatol (1921) with, among others, the future stars Bebe Daniels and Gloria Swanson

Talkie Innovator

DeMille was of the few silent film directors to flourish in the sound era, primarily because he grasped the need for a mobile camera. His first talkie Dynamite was distinguished by its naturalistic sound and fluid camera movement. His first sound epic, The Sign of the Cross, exhibited a masterly use of symbolism, crowds, crane shots, dialectical montage, contrapuntal sound, music cues, sound effects, and even silence.

An early microphone hovers over Claudette Colbert and DeMille on the set of The Sign of the Cross (1932)

The Director’s Director

DeMille was an advocate for directors. He was a prominent member of the Motion Picture Directors Association, the first organization to give directors solidarity. He regularly wrote articles in trade publications on behalf of directors’ artistic rights. He helped found the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1927. In February, 1931, DeMille tried to launch a Directors Guild so that productions could be controlled by “the creative minds in the industry rather than by the financiers,” but the Great Depression halted his project. Five years passed before the Screen Directors Guild (later the Directors Guild of America) was established.

DeMille’s cinematic style influenced artists ranging from Ernst Lubitsch to Woody Allen, Michael Curtiz, and even Alfred Hitchcock. Film historian Kevin Brownlow wrote that Fool’s Paradise (1921) was the “first film that impressed Akiro Kurosawa as a boy.” Steven Spielberg fell in love with movies while watching his first one, The Greatest Show on Earth.

DeMille directs Henry Wilcoxon in Cleopatra (1934)

Master Of Spectacle

DeMille’s immensely popular epics made him the father of the blockbuster. When Steven Spielberg accepted the DGA’s Lifetime Achievement Award on March 11, 2000, he credited DeMille with teaching him how to create epic images. Cecilia de Mille Presley considers Spielberg the DeMille of today. “Like Grandfather, Steven Spielberg has consistently been able to capture vast audiences,” she says. “He has had great commercial success without losing his personal vision or compromising his integrity.”

A scene from This Day and Age (1933)

A scene from Manslaughter (1922)

Producer and Auteur

DeMille imprinted his vision on every frame of his films. While he did not take a writing credit after Forbidden Fruit (1921), he created each scene—sometimes each line of dialogue—with his screenwriters. His voice was consistent and recognizable. “I knew the meaning of ‘plot,’ ‘counterplot,’ and ‘situation,’” wrote DeMille, “long before I could read or write.” Most importantly, DeMille knew how to guide a viewer’s eye to the most important element in any scene, and how to keep that viewer engaged, by telling the story with light, shadow, and movement.

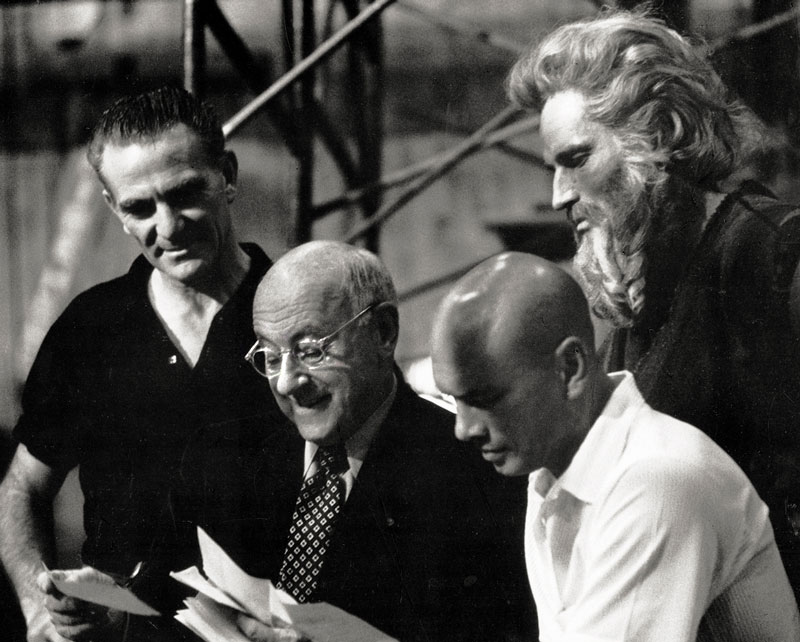

DeMille conferring with associate producer Henry Wilcoxon and stars Yul Brynner, Charlton Heston

Advocate of Women’s Rights and Civil Rights

DeMille valued strong, intelligent women. His mother, Beatrice Samuel de Mille, was a teacher, play broker and writer. Decades before the women’s movement, DeMille employed women in responsible behind-the-scenes positions and for long periods of time, more than any other filmmaker. His collaborators included writer Jeanie Macpherson, aide de camp Gladys Rosson, and film editor Anne Bauchens. His films feature women in active rather than passive roles.

In The Ten Commandments (1956) DeMille shows that a romance has occurred between Moses and an Ethiopian princess. To even allude to the relationship of a white man with a black woman was a radical statement for a Hollywood film in racially tense America. Other scenes include dialogue denouncing prejudice or injustice against “another race, another creed.”

Emily Barrye, script supervisor on numerous DeMille films

Political Presence

DeMille was endorsed by the California State Republican Committee for senator and governor but declined both nominations because he believed he could reach more people through films than through public office. A Boston Herald editorial said that DeMille “is to motion pictures what Winston Churchill is to statesmanship.”

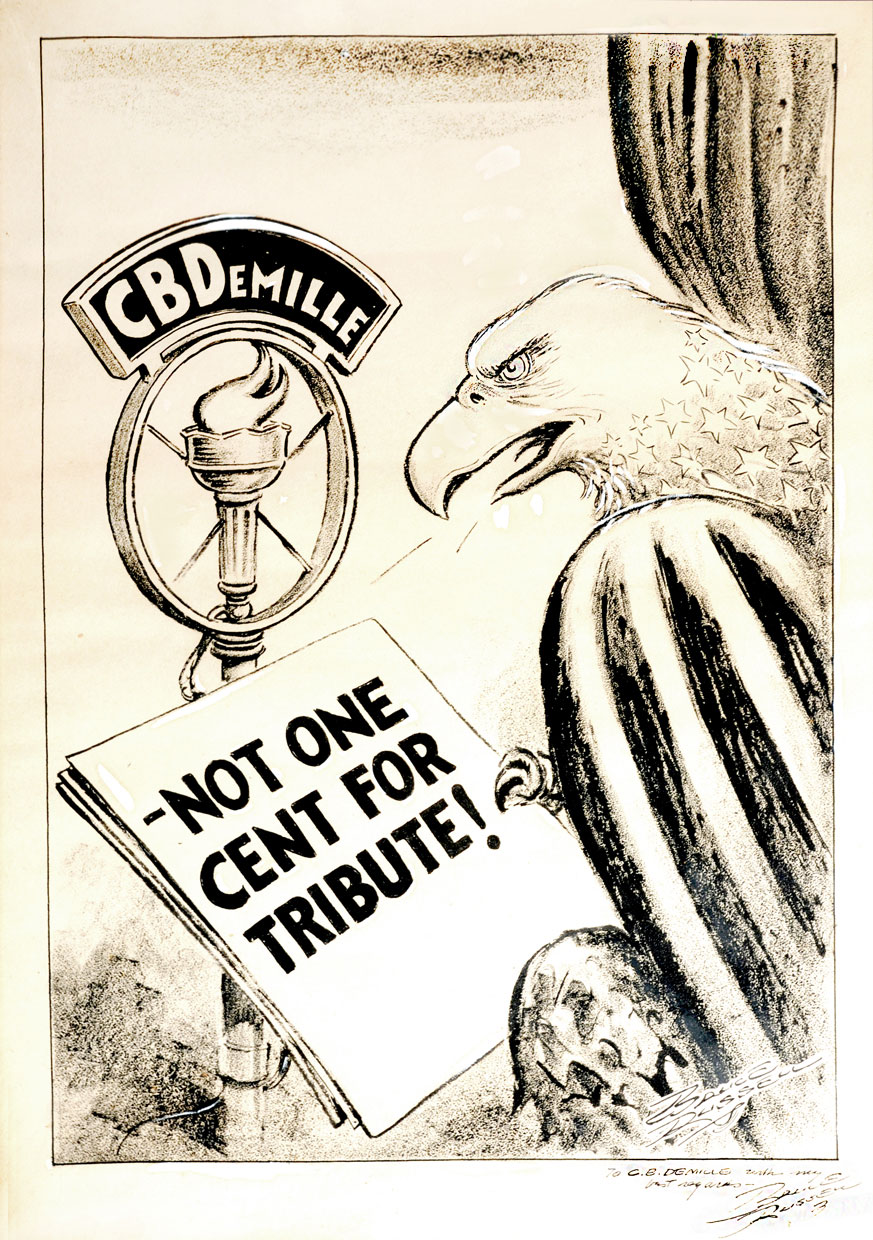

After hosting Lux Radio Theatre for nearly nine years, DeMille opposed the American Federation of Radio Artists (AFRA, later AFTRA) when it required its members to contribute a dollar towards a political campaign supporting the closed shop. Though in favor of unions, DeMille decried political assessment fees and refused to pay the dollar tribute. He was suspended from the union in January 1945. His action cost him the Lux job and banished him from radio (and later television) for the rest of his life. In 1947 Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act, assuring that no one can be denied the right to work for refusal to pay a political assessment. Senator Robert A. Taft said that DeMille’s refusal to pay the dollar had drawn widespread attention to an abuse of union power.

A grassroots movement gave birth to the DeMille Foundation for Political Freedom. When the organization began in September, 1945, only two states had had right-to-work laws on their books. At the time of DeMille’s death in 1959 there were nineteen.

A political cartoon by Bruce Russell

Show Businessman

Maintaining the courage of his convictions also gave DeMille hits at the box office. He was a firm believer in Sir Henry Irving’s line that theatre “must be carried on as a business or it will fail as an art.” But DeMille did not fret over what projects would sell, nor set out to placate studio money men. In good times and bad, he sought to please the American public. Bob Hope once quipped, “Mr. DeMille has brought something new to the movies. They’re called customers.” These customers were drawn by DeMille’s choice of setting, whether ancient Egypt or colonial America. DeMille made no secret of his love for Americana, and it was these films that solidified his financial base in the sound era at Paramount Pictures.

The office of Cecil B. DeMille Productions, circa 1942

Hollywood Preservationist

DeMille’s respect for history led him to preserve not only the nitrate prints of his seventy films but also a great deal of material related to his career. The De Mille Estate has deposited much of it at the Cecil B. DeMille Archives at Brigham Young University. The collection took twelve years to catalogue, and it comprises1200 boxes of organized production files, correspondence, and scrapbooks; more than 8,000 pieces of production-related art; and over 15,000 photographic images. DeMille’s paper legacy is available to scholars from all over the world. DeMille’s ultimate legacy is the effect his films have had on billions of people.

DeMille tending the prints of his films

His Message

DeMille drew from specific scriptural sources only four times: The Ten Commandments (filmed twice); The King of Kings; and Samson and Delilah. Still DeMille is remembered as the maker of biblical epics. He was raised with a love of the Bible, and consequently saw the screen as a universal pulpit. Nothing pleased him more than hearing that he had brought people closer to God. Letters came to him for decades describing the effects of The Ten Commandments (1923). Evangelist Billy Graham was profoundly influenced by The King of Kings. His daughter, the Bible teacher Ann Graham Lotz, said that her conversion as a child took place while watching the film on television. Graham called DeMille “a prophet in celluloid.”

The most abiding aspect of DeMille’s legacy currently reaches people through the medium of television. For more than thirty years The Ten Commandments (1956) has aired during Holy Week on the ABC Television network, gaining high ratings and touching new generations. It continues to resonate with Jewish, Christian, and Moslem leaders, and with lay people of all ages. At the film’s premiere, DeMille said he hoped that those who saw it “would not only be filled with the sight of a big spectacle but also filled with the spirit of truth.” Decades later, the DeMille Foundation still receives letters praising the film’s message of faith and freedom.

DeMille explaining the legend of Moses in a trailer for The Ten Commandments (1956)

The Legacy Continues

DeMille was a young man in the 19th century, yet his influence is felt in the 21st century. Pathfinder and innovator, he changed an industry, a town, and the world. He was, as James V. D’Arc has said, “a man with a mission. Mission accomplished.”

The October 2002 issue of Vanity Fair Magazine saluted Paramount’s ninetieth Anniversary by writing: “Somewhere Cecil B. DeMille is smiling.”

DeMille left a physical legacy in 1923 when, on completing The Ten Commandments, he buried the Egyptian sets in the sand dunes of Guadalupe. He wanted to prevent other companies from shooting on the vacated sets and beating his film to the theaters, but he inadvertently sowed the seeds of an archaeological quest. It began in 1983 and continues to this day. Information about Peter Brosnan’s documentary film on the excavations can be found at http://www.lostcitydemille.com/ Information about Doug Jenzen and the artifact exhibit in the Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes Center can be found at http://dunescenter.org/

In 2014 Hollywood celebrated the centennial of The Squaw Man in the very structure where it had been filmed, the Lasky-DeMille Barn. Variety wrote: “DeMille Is Now a Synonym for ‘Studio Epic.’” He is also a synonym for Hollywood.

Carole Horst article in Variety, January 5, 2015